By: Miles Estrada | Writer (Fiction)

December 14, 2017

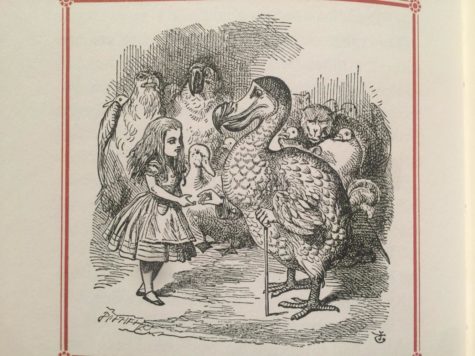

It is no secret that the dodo was a very stupid bird; but it is suspected that, in the earliest stages of its evolution, perhaps it was once not so dimwitted.

As the presents theory stands, the dodo was an antediluvian relative of the contemporaneous pigeon- a bird that, as we know, takes pride in leading a nomadic existence, and has, in spite of their inveterate propensity of multitudinous muting, some small semblance of a cognizant mind. It is therefore speculated that the dodo is itself a descendant of a bird of similar mindset and composition to that of the present-day pigeon.

Given the fact that the dodo had lived in solitude in the sequestered little island of Mauritius off the eastern coast of Africa, this more eruditious bird had most likely made its residence on the mainland, and, with the assumption of predators being in abundance, was capable of flight. It is thence safe to surmise that one day a small batch of them had happened to fly far from the precipitous shores of the continent and, wither before of after they chances to soar over Madagascar, were swept up in a torrid tropical storm, being carried over to Mauritius where they would live out their lives in the dexterous hands of evolution. There, as there existed no larger predatory animals than themselves, these birds prospected, and this the need to flight had become all but frivolous; because of this, their constitution had metamorphosed into a simple, more turgid design so as to acclimate better to the interminable sedentary bliss. And so it was that the dodo lives out it’s placid life, ignorant of any form of carnivorous creatures for ever after, and free to devour all the lizards, frogs, and snails they wanted without the slightest implication of competition.

That was, of course, until, in the seventeenth century, explorers from the Netherlands had embanked off the shores of Mauritius. Their main objective was to colonize the island in the effort of proliferating the rule of the Dutch crown to the farthest reaches of the earth. So colonize it they did, a simple task indeed – given that no man, save themselves, had ever inhabited the island – and thereafter, their rule would reign insuperable but during the first few weeks of their habitation, the resources of the Dutch had been a severely reduced, leading them to venture out into the inextricable jungle to see if a desultory trek could drum up the discovery of an inchoate source of food to live off of. Luckily, their search was remunerative, for they found near the centre of the islands a new means of satiation; the dodo. Now the dodo, being as dim as it was, was naturally quite curious as to the presence of these queer animals, and had never given its perusal of the men a second thought. But perhaps the food should not have been so magnanimous, for by the year 1668, they all went their own way at the hands of the hungry colonizers.

Though that story may seem tired and irrelevant by today’s standards, it is in reality exceedingly prescient of the fate of another species. The tragedy at Mauritius was not the first act of lethal human exploration, and it most certainly won’t be the last. When Columbus has embanked off the shores of the West Indies in 1492, he was met with a strange race of people that was none took heterogeneous from his own, if a bit more tawny; of course, this race had been too inquisitive for their own good, and were all slaughtered mercilessly in a year’s time. In their conquest of Africa and India, the English had unveiled the negroid and Indian races; and within the course of several centuries, they have greatly reduced the numbers of these peoples, and those few that are left struggle for survival presently. But perhaps the most infamous form of exploration in human history is that of the great space race of the latter part of the twentieth century. First, man, out of sheer curiosity, had extended his influence as far as the moon, and had made out well enough; but now, with his intention of venturing out further to Venus and then to Mars, one cannot help but ponder the potential extinction of the human race.

There is an old saying, made renowned by W. Somerset Maugham, which said that if something is good it is unlikely to be new, and if it’s new it is unlikely to be good; and considering what became of the dodo, and what is slowly becoming of man, this statement has never been truer, or more portentous. Perhaps man can learn a thing or two from the dodo, and himself avoid such a lugubrious fate; but of course we can only hope for the better. And judged by the present interest in exploration these days, that notion seems only an illusion.

Lord have pity on us!

Leave a Reply