Savannah Gresham | Writer

March 5, 2021

Cancel culture has been a prevailing attitude in the Western zeitgeist since 2015. But have the people who have championed this digital boycotting really made the world a more inclusive place, as they set out to do?

In order to find the answer to this hotly contested query, we must first understand what it means to be “canceled.”

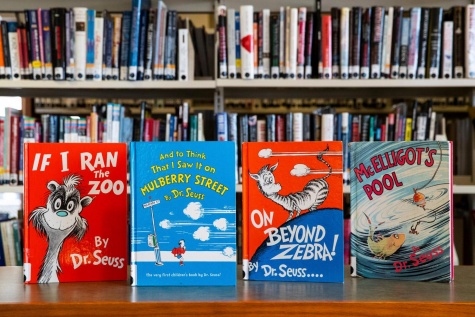

Recently, six books by beloved children’s author Dr. Suess were pulled from the shelves due to racially insensitive depictions of marginalized groups. This begs the question, when is censorship truly justified? Is it better that these works be lost to the tide of time if it means children can grow up in a world that appears more tolerant or is it better that we confront our history in order to learn from it? Or, could there be a third option? Be it a compromise, or something else.

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez asserts this concept as a non-issue in her tweet: “The term ‘cancel culture’ comes from entitlement – as though the person complaining has the right to a large, captive audience, & one is a victim if people choose to tune them out. Odds are you’re not actually canceled, you’re just being challenged, held accountable, or unliked.”

While the open marketplace of ideas is the foundation of democracy, it is immensely easy to find yourself facing off against an angry mob: “Direct questions are the worst. Cops must know this–when someone asks you a question, it is really, really hard not to answer it. It’s even harder when people dig up old tweets and put them side by side with new ones and you can’t really explain the discrepancy…It’s an extremely effective interrogation tactic, and most people make either a tearful apology or an enraged counterattack,” Author Hank Green said.

Freshman Aaliyah Mendoza seems to agree, presenting the idea that cancellation happens on a hair-trigger. “Consequences equal to actions are always warranted – but things work so differently these days. If a celebrity is accused of sexual assault, for example, that’s a good reason for people to stop supporting them or to cancel them. If a celebrity is accused of saying something slightly offensive in an interview 20 years ago and they apologize, I don’t think they should be canceled. Lately, I think people have had a ‘guilty until proven innocent’ mentality which has led to celebrities getting canceled too quickly,” Mendoza said.

It is nearly irrefutable that our society is more polarized now than it has been in recent history. When one group of people rally against something, those who consider themselves that group’s antithesis will support it almost as a formality – as the recent spike in Dr. Seuss sales will attest.

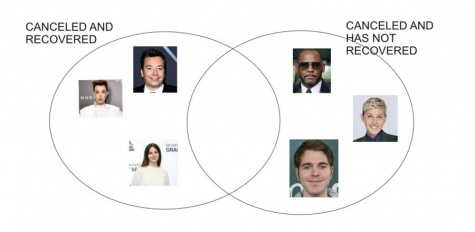

Cancellation of a media figure by one group or platform often leads them to seek and find solace in another. If someone is canceled for one misstep, they are not offered a chance of redemption and reform, they have simply driven away towards those who believe they didn’t do anything wrong in the first place. Once again, this only poses the question of what exactly is being gained from this form of social censorship?

Instead of encouraging development, cancel culture can potentially ruin an influencer’s reputation over dated incidents and humor that was socially acceptable at the time.

“The idea of ‘cancelling’ people for mistakes they have made perpetuates the toxic cycle of placing punishment above learning. A lot of these people are being criticized for things that they have said or done ten years in the past, and are ridiculed even after they have apologized and recognized their mistakes,” senior Riya Khetarpal said. “Our goal as a society and consumers of media should be to hold people accountable, not look down on people who have made mistakes. If we promote education over punishment, we can progress as a society instead of shaming people that will just be ‘uncanceled’ a few weeks later when the next big scandal arises.”

Another negative facet of cancel culture is how it implies the need for perfectionism on all public figures. The need to be unproblematic has been found to outweigh the need for growth. Of course, there are times when this criticism or “cancellation” by the media is justified.

As Khetarpal puts it, “This is not to say that everyone should be forgiven for what they have done; in some cases, the offense is unforgivable or a person refuses to learn. However, we are all human, and it is important that we give people the chance to learn from their mistakes just like all of us are able to. Just because they are in the spotlight doesn’t mean they shouldn’t have the opportunity to make mistakes and grow, too. I don’t like the word ‘cancel,’ but I do think that everyone should be held accountable for their actions. If someone does something offensive or wrong, it is important to call them out on it, so they know that they did something wrong and are not afraid to hold them accountable for it; however, cancelling people whenever they make a mistake is definitely not productive.”

Sophomore Analee Adame holds a similar viewpoint: “I think cancel culture is effective sometimes depending on who the person is. I don’t think cancel culture is achieving its goal all the time. There are times where people cancel someone for a very slight mistake and that just spreads hate towards that person. It’s not really making the world a less offensive place, just a more sensitive place.”

It seems the motivation is well-meaning, but perhaps the key lies in some hybrid of acceptance of history and intolerance toward repeat mistakes in the present and future.

Leave a Reply