Tyler Pearce | Head Editor

May 1st, 2024

Across the United States, college campuses have become the center of political activism and public debate, driven by the latest flare-ups in the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Institutions like Columbia University, George Washington University, Northeastern, the University of Southern California, UCLA, and roughly 110 more have witnessed a significant surge in student-led protests. These demonstrations are part of a broader, decades-long tradition of campus activism, reflecting deeper societal conflicts and often bringing change beyond university boundaries.

The protests, particularly those at Columbia University, are similar to historical campus movements, demanding institutional divestment from entities supporting Israel’s military actions in Gaza. Such demands align closely with the anti-Vietnam War protests of the late 1960s and early 1970s, where students also sought to influence their institutions’ foreign policy stances. The current protesters utilize similar tactics of sit-ins, encampments, and vocal public demonstrations, showing continuity in student activism tactics.

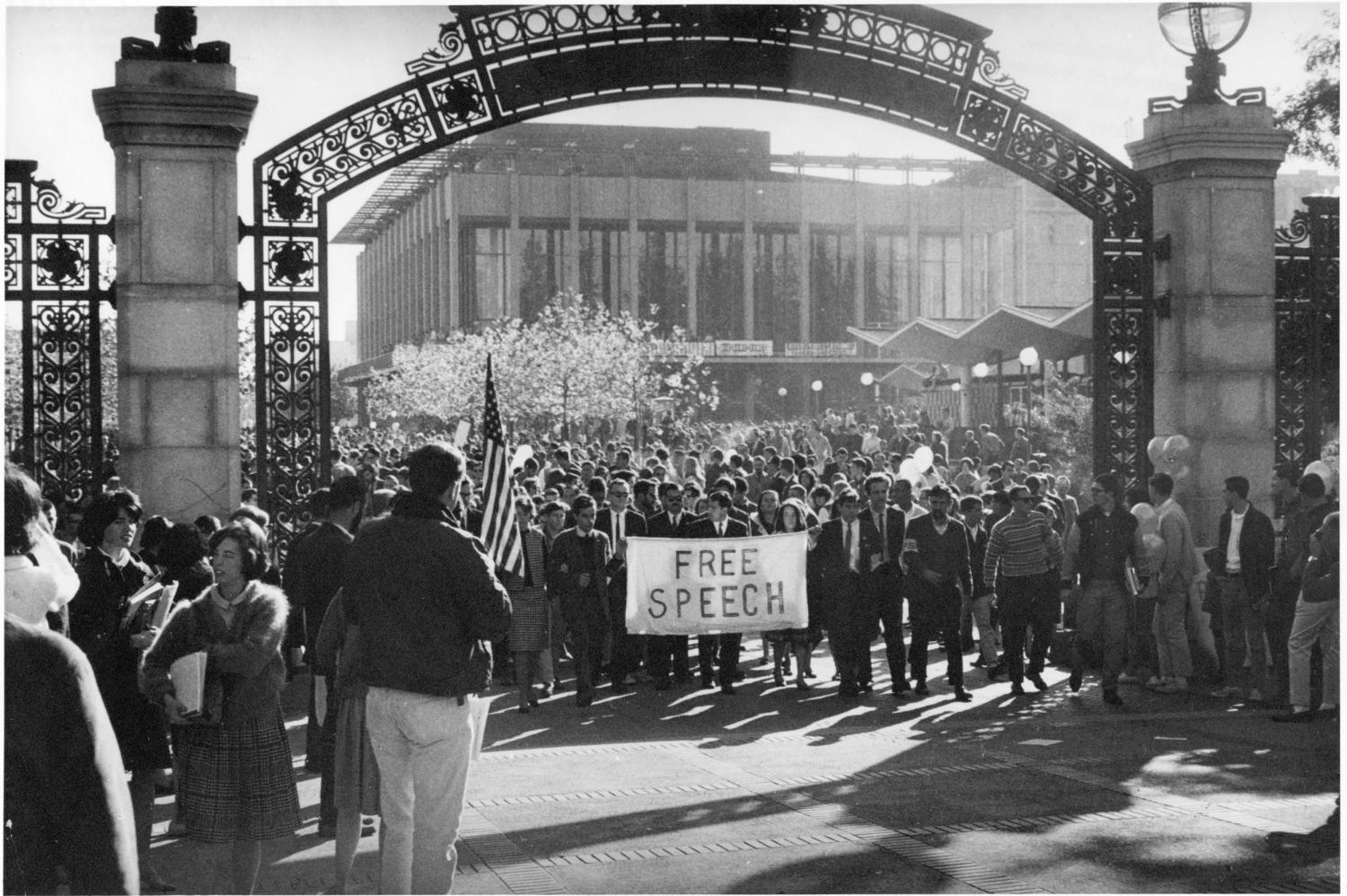

Looking back, the student protests of the 1960s and 1970s—such as those at Berkeley for the Free Speech Movement or the widespread protests against apartheid in the 1980s—often shared themes of anti-imperialism and advocacy for human rights, paralleling today’s anti-war and pro-Palestinian movements.

Senior Sam Poteet states, “I remember on Twitter (X), there was an image of two images next to each other showing 2 student protests at Columbia University. One was about the anti-Vietnam war, and the other was about the current Israel-Gaza conflict. To see the parallels between the two is very interesting to see how the public views such similar actions so differently.” Sam’s Friend Sara Sims agrees and believes that “it’s interesting how in AP US History, we learn about past anti-Vietnam protests and categorize them as “heroic” and “brave”, yet in today’s world, the student protesters are depicted by the media as “privileged students” or “anti-American” or even “Hamas sympathizers.”

Additionally, the role of universities as battlegrounds for these conflicts has been a consistent feature, becoming a breeding ground for progressive thought, and institutions are now caught between new societal values and traditional policies.

Universities’ responses to these protests have varied widely. Today, some schools, like Columbia and George Washington University, attempt to negotiate with protestors, offering compromises to avoid escalation.

Others, like Northeastern and USC, respond with more severe measures, including arrests and campus closures, reflecting a zero-tolerance stance on disruptions. Historical protests have also seen a range of responses from university administrations, mostly confrontational, often influenced by the broader political climate and public opinion.

An exciting aspect of modern campus protests is the alleged involvement of external organizations, which universities claim may bring about tensions. This was also a factor in past decades, where external political groups often played roles in organizing or escalating campus activism. The accusation of outside influence can complicate the narrative, casting doubt on the authenticity of the student movements and potentially affecting public sympathy for the protestors.

The ongoing protests raise questions about the role of higher education institutions in political and social issues. Can universities remain neutral grounds for education, or are they inherently political entities due to their substantial societal influence?

The impact of these protests on campus policies, student recruitment, and public funding remains to be seen. As with historical movements, the effectiveness of these protests in achieving their desired outcomes might shape the political landscape of higher education for years to come.

Today’s student protests are not just about immediate geopolitical events but rather simultaneously profoundly rooted in a history of campus activism stretching back over half a century. They reflect ongoing debates about the role of academic institutions in society and the broader ethical implications of their choices. Whether these protests will lead to lasting changes or fade into history, as many before them, remains present between student activists, university administrations, and the broader societal response.

Leave a Reply