Austin Ashizawa | Student Life Editor

March 18, 2022

This month, many Japanese-Americans will make the pilgrimage to remember the unfathomable acts committed against loyal American citizens during WWII. Perhaps the most shocking part of this look back in history is how closely the atrocity of eighty years prior mirrors events that we continue to see today.

Ever since the breakout of COVID-19, those of Asian-descent have become victims to a dramatic rise in hate crimes which range from the resurgence of repulsive slang to multiple attacks on innocent civilians. And now, with the world uneasily teetering on the thin tightrope of stability due to the situation in Ukraine, hordes of appalling opinions have begun popping up all over the internet. Some people are using the opportunity to harass and berate those of Russian-descent, aggressively lashing out with messages such as “Russians are killers” and “You’re Putin’s Russians.”

To honor the memory of the many who suffered in the internment camps and to again reinforce the consequences of what can happen when blind hatred is allowed to run unchecked, let’s reflect on that dark and cruel injustice in American history.

When the Japanese launched their attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the United States was rudely shaken out of its illusory sense of invulnerability. For the first time in almost a century, the country had experienced a direct military attack. Fortunately, the military was soon poised to retaliate in a war across the Pacific, as soldiers stood ready to avenge the lives of those that perished in the brutal bombardment.

As the U.S. entered the war, discrimination and racism towards innocent Japanese-Americans intensified. A handful of Japanese-Americans had established successful businesses in California after immigrating to the country, some were already second-generation citizens, and others had even joined the military. Yet none of this seemed enough to convince the population that Japanese-Americans were equally as American and as deserving of freedom as everyone else. Thus, in a horrific military move that would supposedly curb “Japanese espionage attempts,” Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, issuing all Japanese-Americans to be relocated to designated internment camps.

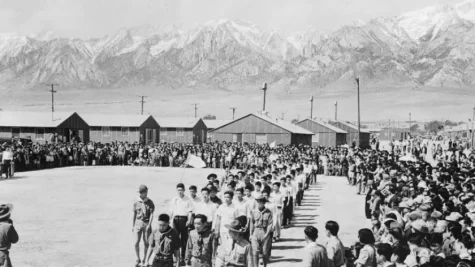

Designated “internees” were given approximately one week to pack their bags with whatever belongings they could fit into a suitcase; anything that could not fit would have to be disposed of. Some were forced to close the doors of their business which would never again see the light of day. Others were forced to leave behind a home that they had worked hard to obtain — one that would no longer belong to them when they returned years later. These over 120,000 citizens were shuttled across the country to distant “relocation centers,” a tremendous euphemism considering that the areas were hardly even industrialized. For over 11,000 of these people, the first internment camp, Manzanar, would be their final destination.

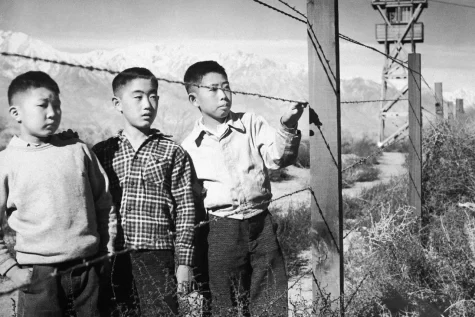

Life for those in Manzanar was far from easy. Although the United States government tried to disguise the atrocity with propaganda films that showed makeshift schools, post offices, and even churches in the camps, the barbed wire and guard towers with snipers that lined the perimeter conveniently remained out of sight. In reality, thousands were forced to wait in long lines to use communal restrooms, receive provisions, and do their laundry. It was utterly humiliating to receive such treatment, and the only thing that these people could somewhat depend on for privacy was the poorly constructed tar paper barracks in which multiple people resided.

Yet regardless of the demoralizing situation, many of the internees found ways to preserve their cultural identity. Some worked to construct crude but beautiful traditional Japanese gardens and ponds that gracefully sprawled across a small corner of the camp. Others sought the chance to prove their genuine desire to be American, with over 12,000 second-generation Japanese joining the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a unit that would go on to become the most decorated in United States history due to their bravery.

By the time the last few hundred internees were permitted to leave Manzanar, the war had already been over for three months. Some had spent almost three and a half years at the camp, and their previous lives were in ruins. With a meager $25 distributed to each internee, Japanese-Americans left the centers with either a one-way train or base fare. It wouldn’t be until 1988 that President Reagan issued a formal apology to surviving Japanese Americans incarcerated in the internment camps, distributing $20,000 to each remaining survivor. Yet these reparations are still insufficient compensation considering that Japanese Americans lost between $149 million and $370 million because of the forced seizure of property during 1942, and that over 1,862 internees died during their time in the camps largely because of unsanitary conditions and a lack of proper health care.

Despite the severity of this injustice, many people still seem to be unaware of nearby Manzanar’s existence. “I have never heard of Manzanar, did we learn about it in school?” one SCHS senior said. “Is Manzanar in Africa?” said another. Unfortunately, the reprehensible events of Manzanar are not a part of some made-up story that occurred in some faraway land. In reality, the site of the camp was located right at the base of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, and you can still visit a shrine dedicated to the camp today. However, these misconceptions from students are not to any fault of their own as the school system, in general, has failed to normalize teaching students the mistakes of their own country.

The United States is not always the hero in the story, and that’s fine; what’s important is that people learn from past mistakes and keep the victims of ignorant actions in our memories. What happened in all of the Japanese internment camps is a chilling reminder of what can happen when hateful behavior is let loose off of its chain. History can repeat itself, and more drastic consequences are sure to follow.

What an excellent article , and so important for your generation of young people to be aware of how fragile our democracy is. We are at great risk of forgetting what happened. Nice to see the President signed a bill to declare one of the internment camps , Camp –

Amache a national historic site