Eden Milligan | Editor-in-Chief

May 2, 2022

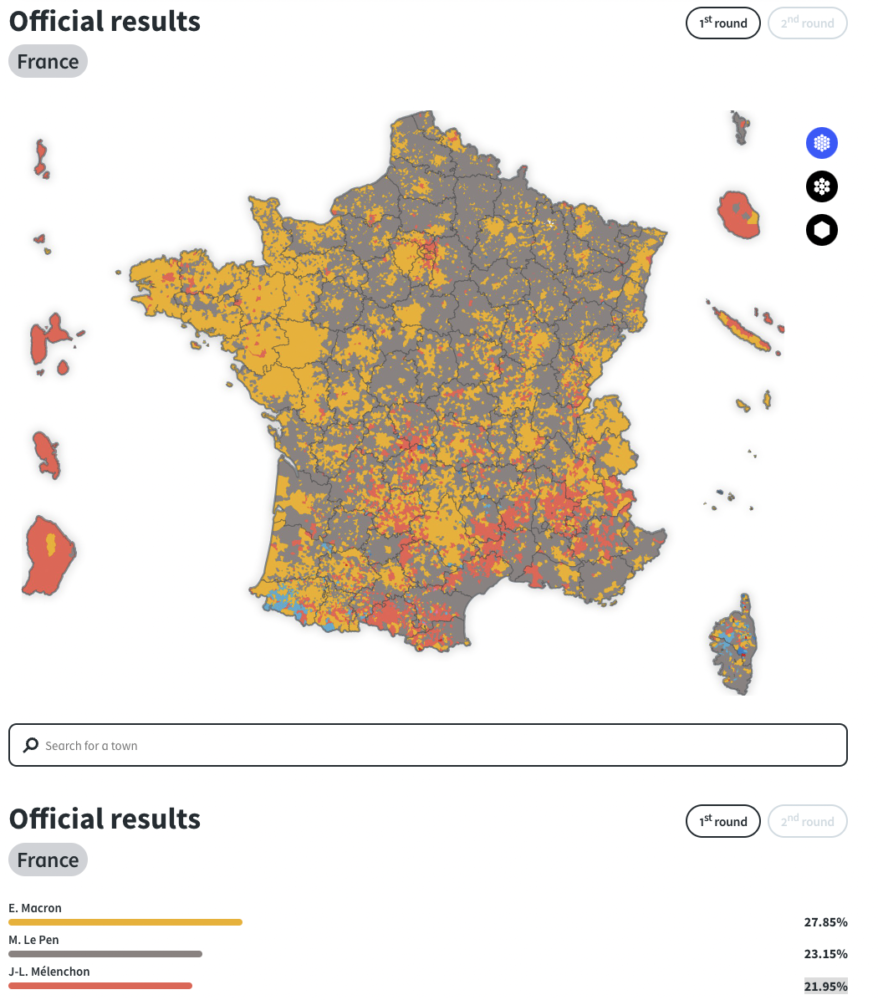

On April 24, the incumbent president Emmanuel Macron became the first president in two decades to be reelected in France. While reelection may seem like a marker of political stability, France experienced a remarkably divided election, with Macron’s opponent Marine Le Pen gaining the most votes for the far-right National Rally party since its creation in 1972.

In France, the position of President is not the same as the position in the United States. When the Fifth Republic was founded in 1958, a dual-executive system was imposed. Under this system, France has both a president, the “head of state,” and a prime minister, the “head of government.” The prime minister is appointed by the president, but the president is limited by the National Assembly’s power to dismiss the prime minister, meaning the prime minister almost always comes from the party in power in the chamber. While some powers, like the nomination of individuals and statutory powers, are “shared” with the prime minister, the president alone is (in practice) the head of national diplomacy. This part of the president’s role was especially significant in the recent election, as Marine Le Pen’s ideology regarding France’s relationship with the rest of Europe and the world were extremely important to her campaign.

France has long had issues with terrorist attacks, and especially in recent years, Islamophobia has been on the rise as a result. At the same time, there is a widespread perception that France itself is “in decline.” In a poll from late November 2021, 62% of respondents said they “don’t feel at home [in their country] like they used to,” and 64% said there are “too many immigrants.” 79% said “there is a need for a strong leader to reestablish law and order.”

Views of what makes a “strong leader” of course differ greatly, but as a general trend, the French public has become more conservative in seeking approaches to the perceived crisis. In another survey from 2021 in which the French described their mood about their nation, the words “uncertainty, worry, and fatigue” dominated. Le Pen promised to quell these sentiments by creating a “government of national unity” by revising the French constitution to ensure “fair representation” of the people. With Le Pen’s proposed revisions, the far-right would gain significantly more power in the National Assembly, creating a more unified government on one side of the political spectrum.

Another way Le Pen planned to fight fear in the nation was by repealing laws allowing illegal immigrants to become legal, reducing the immigration in France linked to asylum rights by 75% and reducing benefits available to immigrants. Le Pen has been long been on the political stage, as she ran for president twice before, and her views on Islam have remained fairly hostile. After the Charlie Hebdo attacks in 2015, Le Pen said that “France and its citizens are no longer safe,” and she (and her father, who ran for president five times) was caught in controversy many times over extreme statements about Islam. In past years, a particular point of controversy has been Le Pen’s proposed ban of headscarves in public places, which would be enforced through police fines. Veiling is a common practice for Muslim women that is supported by international law including Article 18 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, which upholds freedom of private or public religious practices.

While Macron opposes a total ban on veiling, his beliefs about Islam have been far from accepting. Under Macron’s presidency, 750 mosques were closed due to an “anti-separatism” law intended to “free Muslims from the growing grip of radical Islamism.” For many of the five to six million Muslims in France (10% of the French population), neither Le Pen nor Macron seemed to be an acceptable candidate. After Jean-Luc Méléchon, the only presidential candidate who condemned discrimination against Muslims, was eliminated in the first round of elections, abstention rates were high.

“Macron’s separatism laws have unjustly discriminated against Muslim women especially, though he is still viewed as a lesser of two evils against Le Pen,” senior Bethany Padilla said. “This fear of the Middle East and of Islam is embedded in Western politics, especially with the War on Terror, which is rooted in ignorant misconceptions about Islam as a whole.”

France’s fears concerning Islam are not unique to the nation, but they are especially pronounced because France has one of the largest Muslim populations and highest frequencies of terrorist attacks in the West. Still, political ideology in today’s world does not exist in isolation, which is why it is important to consider France’s election here in the U.S. When Trump rose to power in 2017, his rhetoric on immigration was frequently compared to Le Pen’s. Globally, similar conditions create opportunities for similar leaders.

While “stopping uncontrolled immigration” and “eradicating Islamist ideologies” remained the National Rally’s main goals this year, Le Pen’s anti-Islam rhetoric was less severe than in previous campaigns. Recently, Le Pen announced that the hijab ban was “not a priority” and would be adopted gradually. Le Pen’s opinions on globalization also became less extreme in comparison to her 2017 presidential campaign, as she moved from advocating for France’s abandonment of the EU to stating merely that French laws should take priority over international law. This campaign was more focused on economic appeals than in the past, which could account for some of the growth of the party.

“I do think that Islamophobia has contributed [to the growth of the far right in France], but I think it’s more along economic lines that the far right is succeeding, as the poorest areas of France, such as the north, are real strongholds of the far right,” senior Joseph de Traversay said.

In terms of policy in relation to the Russia-Ukraine war, Le Pen has warned against sending weapons to Ukraine and has advocated for increased ties between Europe and Russia which would limit the power of Russia and China’s alliance. In the past, she has explicitly supported Putin, which Macron did not fail to emphasize in debates. Le Pen was quick to denounce Russia at the start of the invasion, but her party’s former ties to the aggressive nation were not ignored.

Ultimately, Macron won by a greater-than-expected margin of 58.55% to 41.45%. However, with two conservative-leaning, harsh-on-immigration candidates, much of the French population either voted reluctantly for the less radical Macron or did not vote at all (about ⅓ of the voting population). Over 8.5% of votes were left blank or null (with names crossed out or ballots otherwise invalidated) in protest.

“I wanted Macron to win over Le Pen, so I am pleased with the results, although none of the candidates really stuck out to me as being good,” de Traversay said. “I know that many people view Macron as an elitist who is out of touch with the average French citizen, and I can understand that point of view. On the other hand, Le Pen is not any better. People are forced to choose who is the least bad candidate instead of who is the best.”

Gen Z had the highest abstention rate of any generation, with 41% of voters aged 18 to 24 not voting. Part of this abstention can be attributed to the demographic makeup of France. “Many young people feel that their votes don’t count as the median age in France is 42.3 years, meaning that there are far more people older than the 18 to 24 range. This makes the votes of those young people less impactful,” de Traversay said.

Another explanation for the decision of young people in France to not vote may be differences in ideals. “I believe, especially from Gen Z, we have seen a lot more condemnation of centrism and the neoliberal perspective,” Padilla said.

Macron has become the modern face of progressive neoliberalism, designing an economic system of “equal opportunity” by promoting human rights in a liberalizing economy. However, many critics of Macronism believe the social and environmental “equality” aspect of his plan has fallen victim to focus on economy building. In general, today’s younger generations are more liberal than their Gen X and Boomer counterparts. In France, these political perspectives do not affect the politics of the majority. “Candidates and politicians know that the people with the power and numbers to put them in office are not the 18-24 year olds,” de Traversay added.

It is therefore unsurprising that the top two candidates catered not to Gen Z’s fears of climate disaster and social injustice, but older generations’ fears of economic instability and excessive immigration.

Even in light of the historic growth of the far-right National Rally party, Macron’s success was yet another testament to the power of relative centrism in a divided political atmosphere. With political radicalization on the rise and drastic swings between liberalism and conservatism creating conflict across the West, those who vote out of fear of the more radical opponent, in the U.S. and in France, seem to have the upper hand in deciding elections.

Leave a Reply